Why literature matters – Thoughts on Szabó Magda (University Essay – London, 2024)

“I wanted to free my country from a war in which there are no heroes, only victims” (Szabó, 2020)

As Hungary’s most translated author, Szabó Magda is well known all over the world. Her book The Door (Szabo, 2015) has been made into a big screen movie, starring Helen Mirren in 2012. However, the most beloved book by Szabó is not the big production The Door (IMDb, 2016) or the heavy, emotional Liber Mortis (Szabó, 2012), it is Abigél (Szabó, 1970), which has become a cornerstone classic of Hungarian literature.

Interpretation as a child reader

As a child reader Gina’s story made me understand many things about the world, the life of adults did not seem so secret anymore. Abigail (Szabó, 2020) is a double-edged sword of learning, understanding, and presenting outdated lives. From the viewpoint of a child reader today, the story can be unfortunately timely, as we live through multiple wars across the globe. The teaching quality of the story is easily identifiable and lends an easy to digest lesson for children who try to understand the complexities of war.

This quality is familiar to readers of The Chronicles of Narnia (Lewis, 2015); or The boy in the striped pyjamas: a fable (Boyne, 2008) where the protagonist is oblivious to the horrors around him. “‘The Fury,’ said Bruno again, trying to get it right but failing again. ‘No,’ said Father, ‘the— Oh, never mind!’ ‘Well, who is he anyway?’ asked Bruno again. Father stared at him, astonished. ‘You know perfectly well who the Fury is,’ he said. ‘I don’t,’ said Bruno.” (Boyne, 2008) Abigail (Szabó, 2020) remains much closer to reality, presenting a story close to auto-fiction, rather than fantasy adventure. “Gina, we have lost the war. In truth it was lost from the start. Its aims were always bad, and so has been the way it has been conducted. We have lost so many lives now that God knows when the country will recover, and we are not yet at the end of it. There is nothing left but to try and save as many people – the people in our towns and cities and the soldiers on the front – as can be saved, before the Germans invade and occupy the country.” (Szabó, 2020) This realistic footing allows child readers to have a more understandable lesson about war and does not infantilize the horrific events that may unfold around a child; however, this again is a double-edged sword, as child readers today, especially in Western society, are becoming generally desensitized to violence due to media consumption and video games. (Pittaro, 2019) Therefore, parents and educators must ask themselves if it is the correct course to introduce a young reader to war through this channel. It may be that today’s children are unable to identify themselves with Gina’s character, as she seems too fictional for them, especially as the behavior and mannerisms of children are so different today from children of the 1940’s.

Issues regarding accuracy and representation

As Hannah Randall explains, there are significant problems with young adult/children’s fiction and historical context. “As a young German boy, and the son of a senior SS officer, Bruno would have been, by law, a member of the Hitler Youth. He would have attended a German school where students regularly swore oaths to Hitler and where antisemitic propaganda infiltrated every part of the curriculum.” (Randall, 2019) This issue similarly exists in Abigail (Szabó, 2020). Even if Gina were sheltered and privileged enough to not care much about the war, she would be very much aware of the country’s situation. Similarly to German children at the time, Hungarian children were taught and often propagandized in school. The spread of propaganda in schools is represented in Abigail (Szabó, 2020) when one of Gina’s teachers discusses the duties of a proper young Hungarian girl. The fictionalization of these children’s ideas about war may represent an invalid image for young readers today, which in turn may cause young readers to think that children of the past were stupid and consequently later they may believe that these children who are our elderly today are ignorant or misinformed.

Interpretation as an adult reader

The interpretation of Abigail (Szabó, 2020) outside of Hungary usually differs from my personal understanding and the understanding of other Hungarian readers. Oftentimes the book is labelled as ‘girl fiction’ or ‘book for girls’ and ‘young adult novel.’ The idea that this book is written for young girls comes from the protagonist and other main characters being young girls around fourteen. However, forgetting the theme of the book seems to be a mistake many reviewers make. Gina is not simply an average fourteen- year-old girl, she is the daughter of an army general, who hides a grave secret from his daughter. He is part of the resistance, fighting against nazi propaganda, trying to get Hungary out of war, trying to protect young men from inevitable death on the battlefield. “STOP THIS POINTLESS SHEDDING OF HUNGARIAN BLOOD! WE HAVE LOST THE WAR. SAVE THE LIVES OF YOUR CHILDREN FOR A BETTER FUTURE.” (Szabó, 2020) When Gina is faced with these words, it feels as if the reader is standing in front of the statue, looking at the defiant words of resistance as Szabó’s writing evokes an absolute feeling of reality.

The story carries the powerful entity of the past; however, it becomes harder to connect with Gina on a personal level as her actions and thoughts seem childish and far-removed from the adult reader, and the story’s time setting becomes far-removed from us as we leave World War II behind. However, Gina’s actions are not the only far-removed element of this story. Even for the Hungarian reader, Gina’s lifestyle is unfamiliar. “Her first loss was Marcelle – the Marcelle she had always addressed as “mam’selle,” though she had never thought of her as simply the young Frenchwoman who for twelve years had slept in the room next to hers and had brought her up.” (Szabó, 2020) Afterall, few, if any adults today had live-in governesses. The idea of growing up in a mansion, looking down on the Buda hills is unimaginable to most today in Hungary. The same can be said about closed religious boarding schools as religious institutions differ significantly from the schools of 1943’s. However, we must remember that these elements were fitting for the time of first publication in 1970. Adult readers were able to identify with Gina’s story because they lived through the war and were around the same age as Gina, and they could connect with their children or even grandchildren through Gina’s adventure. Today this is much harder, as adult readers don’t have personal memories of World War II.

Personal understanding and significance

On a personal note, this book and the television movie series based on it carry enormous significance in my family. My father forbids playing the movie while he is in the house after repeatedly listening to it for over a decade (although he still eventually sits down to join us when we sneakily put it on), and every time we quote a line from the book with my mother, there is a fee to be paid in the infamous ‘Abigail jar’ that stands on the kitchen counter. When I was ten years old my mother handed me Abigail for the first time. Before allowing me to devour the book, she warned me that this one is different from books I have read previously. She told me, this one is painful, full of memories yet unfamiliar to me. She told me I can come to her with any questions I have, and she will answer truthfully. After finishing the book for the first time, I was in shock for days. We learnt about World War II in school by that point, and my great- grandmother told me the child friendly versions of her stories, but I had never expected to face such a fictional yet realistic story of someone close to my age living through the horrors of war. Like every other young teenager, there was nothing worse than my own teenage experience.

Years later, at age fourteen, I entered high school and found myself at an above average level of literary understanding. Luckily, this was recognized by my wonderful teacher, who has since become one of my best friends. A prestigious literature competition was approaching at the end of the first year of high school, which I was persuaded to enter. I chose Abigél (Szabó, 1970) to be my subject, and it was at that moment my obsession with this book began. This obsession I carry with me to this day. As an adult, I have re-read the book countless times. The memories surrounding it bring me an incredibly special sense of belonging and joy. Yet, as I become older the book morphs with each reading. I now notice some parts where the writing is too simple and less exciting. I recognize that this may be due to the countless amounts of re-reading as I am so familiar with the story the excitement of the unknown is lost. However, to this day, I return to Gina in times of distress or if I just need to see a familiar face.

Bibliography

Boyne, J. (2008). The boy in the striped pyjamas : a fable. London: Definitions. Gömöri, G. (2007). Magda Szabó. The Guardian. [online] 28 Nov. Available at:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/nov/28/guardianobituaries.booksobituaries [Accessed 16 Apr. 2024].

IMDb. (2016). The Door. [online] Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1194577/.

Lewis, C.S. (2015). The Chronicles of Narnia. London: Harpercollins Children’s Books.

Pittaro, M. (2019). Exposure to Media Violence and Emotional Desensitization. [online] Psychology Today. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-crime-and-justice-doctor/201905/exposure- media-violence-and-emotional-desensitization.

Randall, H. (2019). The Problem with ‘The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas’. [online] Holocaust Centre North. Available at: https://hcn.org.uk/blog/the-problem-with-the-boy-in-the-striped-pyjamas/.

Rothfeld, B. (2020). In Magda Szabo’s Magical Novel, a Statue Protects Students From the Nazis. The New York Times. [online] 17 Jan. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/17/books/review/abigail- magda-szabo.html.

Szabo, M. (2015). The Door. New York Review of Books.

Szabó, M. (1970). Abigél. 1st ed. Budapest: Móra Ferenc Ifjúsági Könyvkiadó. Szabó, M. (2012). Liber Mortis. Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó.

Szabó, M. (2020). Abigail. MacLehose Press.

Diversity in YA publishing (University Essay – London, 2024)

In the following report are my findings regarding diversity – focusing on people of color authors – in YA literature publishing.

Before looking at the audience and authors, let me somewhat define what YA literature means: usually YA literature is for teens aged 13 and above, all the way to young adults in their twenties. „The chief characteristic that distinguishes adolescent literature from children’s literature is the issue of how social power is deployed during the course of the narrative.”[4]

„Adults create these books as a cultural site in which adolescents can be depicted engaging with the fluid, market-driven forces that characterize the power relationships that define adolescence.” [4] I believe that Seelinger has hit crucial points in defining what YA literature is; as the decision to include diverse content ultimately falls on the author, and the authors of YA literature are adults, publishing the book and getting it to shops also falls on adults, as well as in most cases allowing the adolescents to purchase and read the book. The adults shaping the industry, therefore, need to be as diverse as the adolescent readers, otherwise, the issues in the industry regarding diversity will not change. Re : Thinking ’Diversity’ in publishing, a report by Dr Anamik Saha and Dr Sandra van Lente from the University of London, opens its ’Main Findings’ section with the following statement: „Assumptions about audiences: The core audience for publishers is white and middle-class. The whole industry is essentially set up to cater for this one audience. This affects how writers of colour and their books are treated, which are either whitewashed or exoticised in order to appeal to this segment.”[5]

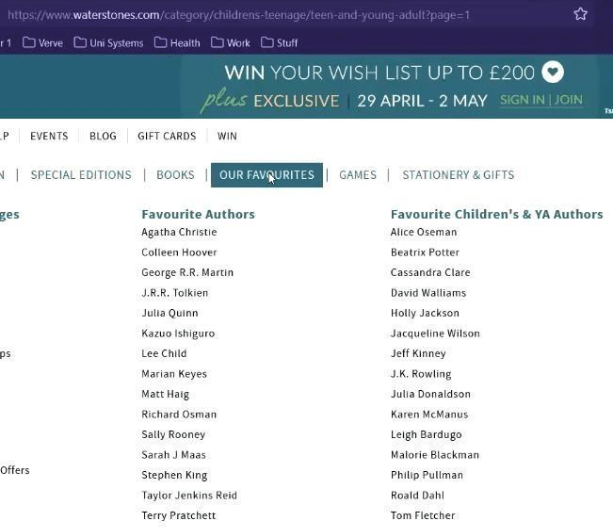

An important part of this is that the audience reached should be as diverse as possible, however, unfortunately most bookshops that actively promote books written by diverse authors – Gay’s the word, Knights of and similar – are not well known and do not have the funding to reach a similar sized audience as large chains. I have examined the largest English chain, Waterstones. Waterstones do not represent author diversity – at least on their website – as you can see in the following list of the first 10 authors found in the ‘Teen and YA books’ section: Alice Oseman, Leigh Bardugo, Kathleen Glasgow, Jennifer Lynn Barnes, Karen M. McManus, Adam Silvera, Sarah Underwood, Sarah J. Maas, Malorie Blackman, Erin Moregenstern.[6] From these 10 authors, only Malorie Blackman and Adam Silvera are not white. That means only 20 percent of the first 10 authors the audience comes in contact with on one of the largest bookseller’s website are representing diversity. I would also like to highlight that most books on page 1 of my search – where I have not entered any filtering criteria – are books of Alice Oseman; to be exact, out of the 72 books on page one of ’Teen and YA books’ category, 7 are Alice Oseman’s, which represents 10.2 percent of the page. The first book on this page is Heartstopper volume 1 exclusive edition by Oseman, however all other volumes of Heartstopper also appear within the first 3 rows on the page, including Heartstopper basic edition. As we can see, a single author occupies half as much (percentage of) space with her books on the first page as there are non-white authors – in the first 10 authors – of the same page.

I understand that some may look at my findings and say that these authors and books on page one of ’Teens and YA books’ category are there because this is what people search for and that picking out a singular store/brand is insufficient. However, I would like to highlight that for this assignment, due to the limitations in word count I have decided to only look at Waterstones, as it is the largest bookseller store in the UK and according to their own site „an icon of the British cultural landscape”.[6]

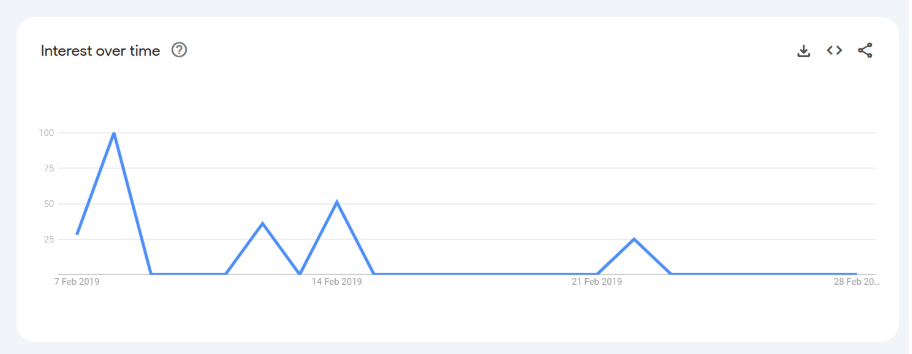

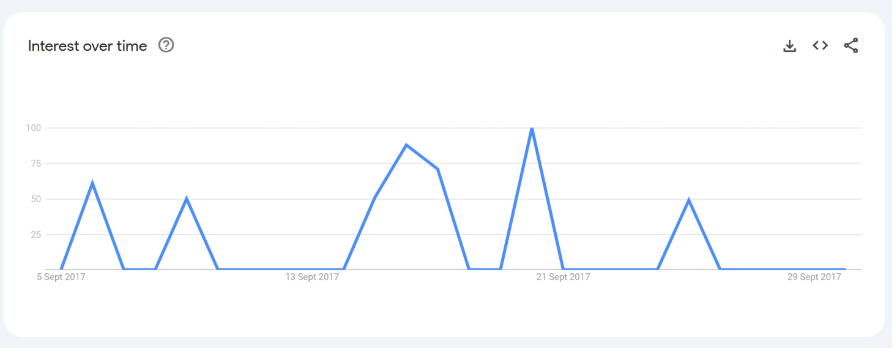

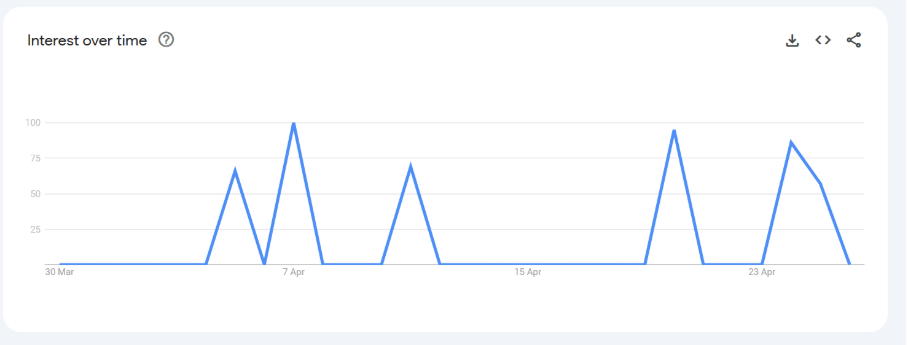

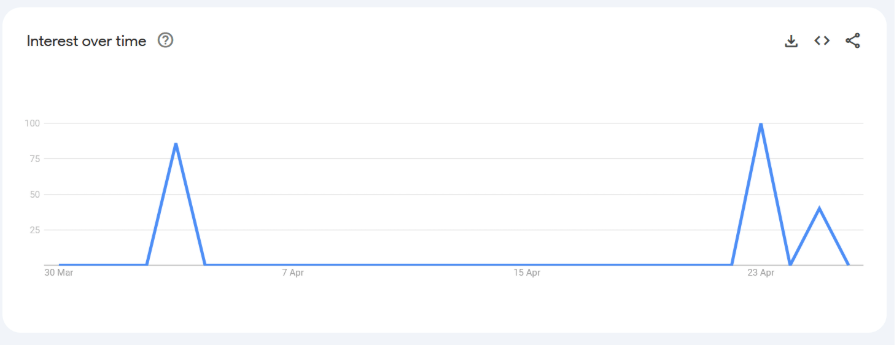

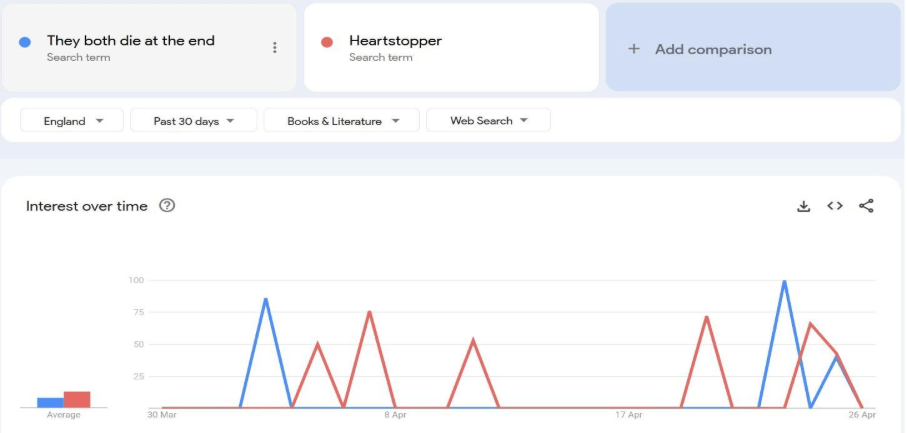

To cover the arising questions regarding people’s searches and what is popular on the internet I have looked at the largest search engine’s (Google) search statistic site. We can see in the appendix attached on Figure 1, the google searches for YA books a day after the publishing of Heartstopper, the searches for it reached peak immediately, whereas if we look at for example Silva’s book on Figure 2 in the appendix, They both die at the end reached peak search on the 21st of September, which is 16 days after publication. Figure 3 in the appendix shows the searches in the past 30 days for Heartstopper and Figure 4 shows the same for They both die at the end. Figure 5 shows Figure 3 and 4 together, where it is clear that Heartstopper outweighs They both die at the end. In conclusion, from these findings I can report that the placement and push on store websites clearly influence the level of awareness around a book and that after publication the focus of advertisement completely shift towards the capitalist ideal, disregarding the influence of the advertised books on the young readership.

After looking at the above figures I have also looked at the ’Our Favourites’ menu, specifically the ’Favourite Children’s & YA Authors’ on Waterstones’ website. At the time of access, the top 10 authors in the favourites section were 100 percent white, this is demonstrated on Figure 6 in the appendix. I can clearly determine from these findings that the recommendations made by chain stores and large companies is clearly catered towards a white audience and favours white authors, and is completely focused on earning money, rather than education.

„Today, as our society changes, and reader demographics shift, there is no more important an issue facing the book business than the diversity of its workforce and the make-up of the books that are published.”[5] – reads The Bookseller’s statement in Re : Thinking ’Diversity’ in publishing; however, unfortunately, as we can see from the above finding,, that any effort to change done by the publishing industry is ultimately crossed out by corporate greed.

„When we investigate how social institutions function in adolescent literature, we can gain insight into the ways adolescent literature itself serves as a discourse of institutional socialization.[4] Looking at the publication industry as an institution, it is clear that more effort is required to change old, exclusionary practices as that it is important for the future generation to see diversification not only in the content of the literature they read, but also the adults that provide that material, as we know that adolescents learn and rely on not only their parents in learning how to navigate the world, but also educators around them. I believe that authors are educators in the sense that the books they produce shape the adolescents that pick the books up from the shelf.

In conclusion, I acknowledge that the pool of information was much constrained for this research and that the overall industry-wide figures may differ. However, I believe that for this research, the small pool of information was also beneficial as I was able to present a key industry operator’s influence not only on the market, but the consequently the young readership as well. It is obvious from reports like Re : Thinking ’Diversity’ in publishing that the industry is trying to accomplish change regarding diversity, however, unfortunately it seems that if large corporations are unwilling to leave the capitalist ideal behind, fighting for diversity is a one- sided, lost battle.

Appendix

Figure 1, Seach interest of Heartstopper within 30 days of publicationn date [2]

Figure 2, Search interest of They both die at the end within 30 days of publication date [2]

Figure 3, Search interest of Heartstopper within last 30 days (from 30.04.2023) [2]

Figure 4, Search interest of They both die at the end within last 30 days (from 30.04.2023) [2]

Figure 5, Comparison of searches within past 30 days (from 30.04.2023) [2]

Figure 6, Watersones favourite authors from waterstones.com [6]

Bibliography

- Bloomsbury Publishing (2022). Writers’ & Artists’ Yearbook 2023. Bloomsbury Publishing, pp.407–475.

- Google Trends. (2015). Google Trends. [online] Available at: https://trends.google.com.

- May, J.P. (1995). Children’s literature and critical theory : reading and writing for understanding. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Roberta Seelinger Trites (1998). Disturbing the Universe Power and Repression in Adolescent Literature. University Of Iowa Press.

- Saha, A. and Van Lente, S. (2020). RE:THINKING ‘Diversity’ in Publishing. [online] Available at: https://www.spreadtheword.org.uk/wp- content/uploads/2020/06/Rethinking_diversity_in-publishing_WEB.pdf.

- www.waterstones.com. (n.d.). Teenage and Young Adult Books | Waterstones. [online] Available at: https://www.waterstones.com/category/childrens-teenage/teen- and-young-adult [Accessed 30 Apr. 2023].

ABOUT US

@ Copyright & Terms and Conditions